Education in the age of Covid-19 – A case study in coping with the disruption

Before Covid-19 struck, and despite the need to prepare young people to live and work in an increasingly digital world, some, perhaps too many, education stakeholders were ambivalent and even dubious about the value of remote and digital learning. Some saw it as the thin end of a wedge in which computers replace teachers and educators; young people spending evermore time in front of screens for study as well as play.

However, the pandemic has demonstrated that the ability to educate remotely adds resilience and minimises the social costs of interrupted education. It has provided examples of good practice and positive impacts in general education, Technical Vocational Education and Training (TEVT) and Higher Education, from many countries including Uruguay, Pakistan and Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, pupils, even in well developed countries, tell us that the experience has been mixed.

Effective Partnerships

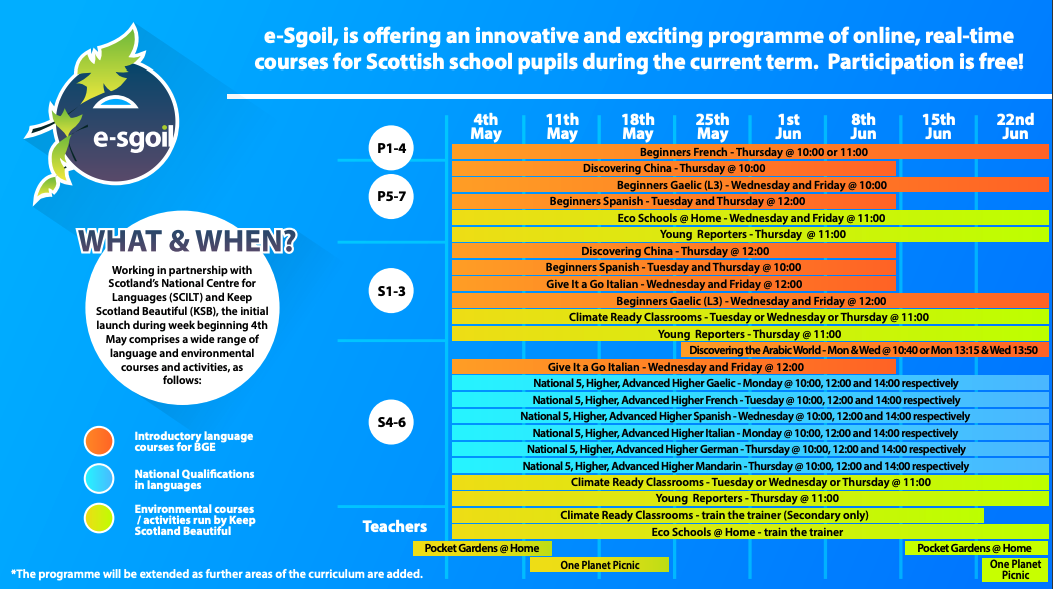

The value of blended learning is demonstrated amply by e-Sgoil, the remote teaching ecosystem which grew from a desire to provide equality of access and participation for pupils in rural communities scattered across Scotland’s wild Western Isles. E-Sgoil uses the national digital education platform GLOW, and commercial education collaboration software Vscene. Partnerships with public and third sector developers of curricular resources as Scotland’s National Centre for Languages (SCILT) the Confucius Institute (CISS) both based at the University of Strathclyde, Keep Scotland Beautiful, and SCHOLAR, have enabled it to launch a wide range of language, environmental, and cultural content to pupils in Scotland and beyond. Uptake by pupils – often without prompting from their own teachers – has been remarkable.

E-Sgoil’s most recent initiative is fully subscribed, so too is a parallel program of professional development for teachers. While parents were being bombarded with websites that could help, these partners in e-Sgoil recognised the need for learner structure, within a timetabled real time teaching experience. From a standing start and at very little additional costs, a new school was created for Scotland; oversubscribed in some classes within a week. By the 6th of May, 15,364 young learners aged 5-18 from all 32 Local Authorities had been involved in this new school, almost 500 were on a waiting list, and just over 300 teachers were enrolled for professional development activities.

Lessons to be learned

What lessons can we draw from such examples of good practice?

The first lesson is that education systems which already had an embedded digital culture made the transition from blended learning to remote learning far more smoothly and effectively than those who found themselves making the transition from traditional learning as an emergency measure. Examples of good practice include Plan Ceibal in Uruguay and e-Sgoil.

A second lesson is that there is no need to spend time and effort developing bespoke content and platforms – high quality educational resources are widely available on digital and broadcast channels such as BBC Bitesize. Excellent virtual learning tools such as Moodle, Padlet and Google Classroom are easy to adapt to local context and curriculum. Connectivity solutions can always be found and need not be digital, as the examples of Pakistan and Uzbekistan show. The appeal with e-Sgoil has been the real time pedagogic interface between the educators and the learners focused on curriculum offers that are appealing and recognisable in their educational systems.

The third lesson is the importance of partnership. The success achieved by e-Sgoil is attributable to its leverage of partnerships to provide educational resources; Scottish Government’s commitment through its Deputy First Minister has been crucial. This allows e-Sgoil’s small staff team focus their energy on developing the teaching methods and equipping teachers and pupils with the skills needed to operate in a remote learning environment. As in every educational setting, the degree of success is a function of the skills of the teacher. Whilst some sources highlight concerns, e-Sgoil has identified some key points of guidance for effective remote teaching.

The fourth lesson concerns coordination and management. Teachers operating in the ‘new normal’ have commented on how the balance of their workload has changed and the highlighted the importance of effective communications with parents and pupils, especially in areas of high deprivation and when supporting the most vulnerable pupils. There are opportunities for efficiency though, such as by ensuring that pupils all use the same online platform. For example use of GLOW (the national digital learning platform) was found to be patchy across Scotland, and this had to be addressed for pupils outside the Western Isles accessing e-Sgoil. Coordinated timetabling is essential for remote teaching across multiple schools as is technical back up in the first few course lessons when human error can impact on the learning experience.

Looking Ahead

In conclusion, traditional education systems have evolved over decades if not centuries, and they are generally poor at coping with emergencies. The Covid-19 crisis has precipitated innovation and development at an unprecedented pace, and has demonstrated the potential for remote learning within a blended learning environment as a tool to enhance access. It is very likely that in many global educational systems the ‘ new normal ‘ will be around for many months and hopefully one of the positive legacies of Covid-19 will be an acceptance that blended learning, where there is direct interface between educators and learners no matter distances, can be firmly established.

Every education system would do well to ask how it can improve its remote learning capability to improve resilience in emergency situations, and help minimise the social costs of interrupted learning. The best examples focus on developing teachers’ skills, and leverage partnerships with a range of organisations in the public, private and third sectors to meet the learning needs of pupils.

About the Authors

Martin Finnigan is Director of Caledonian Economics. He works with governments and international development agencies, developing better partnerships in the education sector.

Bruce Robertson is a former Director of Education and a Visiting Professor at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland.